Calendar of Swabia

In some records you may find alternate names for the months. These are Germanic names, established by the Emperor Charlemagne in the 800s:

January = Hartung, also Horn, grosser Horn and Jänner (sometimes written Jenner). Jänner is still in use.

February = Hornung, also kleiner Horn, sometimes Hornig (in the Sundgau)

March = Lenzig

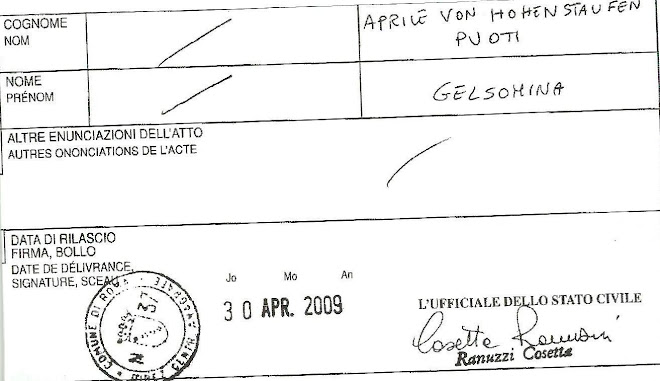

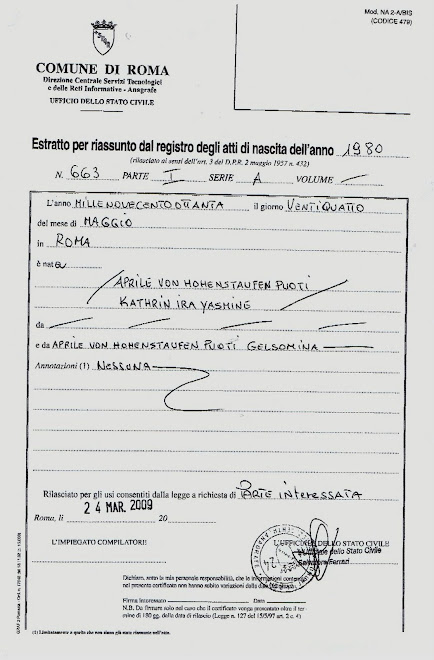

April = Ostermond (Pasqua -Luna -Pasqua in Greco e'Paraschevi o Verdi,ovvero Venere .Luna o Orbita o uovo, quindi uovo o stirpe di Venere(Veiblinghen o Staufer Ex aufer , Dalla coppa di Freya )

May = Maien

June = Brachet

July = Heuert

August = Ernting

September = Scheidling

October = Gilbhard

November = Nebelung

December = Christmond

databases Literature-DB

Swabia (Medieval Duchy)

From GenWiki

General Information

Description of the research area

Swabia [sway'-bee-uh] (German Schwaben, Latin Suevia), with its capital at Augsburg, was a medieval duchy in the lands now forming southwestern Germany. Its territories covered the area now occupied by Baden-Württemberg (the Black Forest) and parts of western Bavaria (to the Iller River) and northern Switzerland. It owes its importance to its strategic position between the upper reaches of two of Europe's most important rivers, the Danube and the Rhine.

History

The region was first known to the Romans as Alamannia because at the time its settlers were the Germanic tribe of Alamans. When the Romans began to conquer the area, it was incorporated as part of the Agri Decumates. It later received its present name from later German migrants, the Suevi, who became amalgamated with the Alamanni in the 5th century AD.

These Suevi are probably actually best thought of as a collective group of a number of German tribes (including the Marcomanni and Lombards), which are mentioned in the 1st century BC by Gaius Julius Caesar as dwelling east of the Rhine River. The Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (1st century AD) described them as inhabiting all of central Germany. One group of Suevi, allied with the Vandals and the Alans, swept down on the Iberian Peninsula in AD 407, conquered it from the Hispano-Romans living there, and apportioned out the territory. As a result, by 411 Suevi were established in present-day northern Portugal (with capital at Braga) and Galicia, and by 452, in Castile. Names such as Loivos, Atães, Rendufe, Adaufe and Gondomar testify to their presence. They adopted Catholic Christianity and ruled until 469 when they were subjugated by the Visigoths, who had been co-opted by the rulers at Rome. The Suevi, and Alamanni, who remained in Germany are the ancestors of the medieval Swabians. The name is also spelled Suebi.

Around 500, Alemannia came under the control of the waxing Frankish Empire. But its ruling house, the Merovingians, were not strong and by 689 Swabia was virtually independent. It was brought back under control in the 730's and 740's by Charles Martel, founder of the Carolingian Dynasty, who deposed the hereditary dukes of Swabia and subdivided it to be ruled by counts reporting directly to him. This situation continued until the 9th century and the dissolution of the Empire under the grandsons of Charlemagne. Between 900-11, largely because the central royal authority failed to stem the tide of invading Magyars (Hungarians) and Normans, the Alemannians were able to become an independent "stem-duchy", organized, like those of the Bavarii, Franks, Saxons and Thuringii, around the people of an historic tribe.

As in all the duchies, the dukes were those who proved they could meet the miltary demands of those anarchic times. The first duke's family were known by the sobriquet dux Raetianorum, i.e. defenders of the Alpine passes of Switzerland, reflecting their role as military leaders and organizers. During this period, Swabia controlled not only parts of Switzerland, but lands west of the Rhine River, i.e. including the Alsace. Alemannia's forces raised its commander, Erchanger, to the dukedom in 915, after his forces defeated the German king Conrad I. When Erchanger was defeated and executed in 917, he was replaced by Burchard II, who had strong enough backing to actually have made a play for the monarchy. Instead, he decided to accept the choice of Henry I of Saxony made by the dying King Conrad I.

In 919, Burchard was faced with the challenge of invasion by Rudolf I, king of Burgundy. Alemannia successfully repulsed the invaders and the peace that followed was sealed by the marriage of Rudolf and Burchard's daughter. The two formed an alliance and began expeditions to conquest in Italy about 922. When four years later Burchard died during one of them, his ally Rudolf pressed his claim to Alemannia through marriage. However, Henry was unwilling to see Alemannia alienated from the kingdom and instead appointed as duke, Hermann, cousin of Eberhard who hailed from Franconia. Hermann showed his gratitude in 919 by saving the fortunes of the king during the Saxon Revolt. But his installation had inaugurated a regular trend -- between 926 and 1080, only one duke was Alemannic, all the rest were either Franks or Saxons. Meanwhile, to assuage Rudolf's ambitions, the town of Basel was severed from Swabia and given to Burgundy. In gratitude, Rudolf presented Henry with an artifact recovered from Italy -- the Holy Lance, an important symbol of the inheritance of Constantine.

But Swabia, as it now began to be called, still managed to be sovereign enough to pursue its own foreign policy. Liudolf became duke in 949, succeeding Hermann by marrying his daughter. In 951, Liudolf crossed the Alps, ostensibly to champion Adelaide of Burgundy, but in reality to take advantage of Italian weakness to expand his realm. He was pre-empted in this when the king, Otto I, himself invaded the region, secured the crown of Lombardy and married Adelaide. The duke, who was Otto's son, transformed his disappointment into first a conspiracy in 952 and in 953 an open revolt which could not be quashed until 955. Only following this did Otto feel strong and secure enough to go to Rome and become the first German king to be crowned by the pope as a nominal emperor.

Another of the Burchards took over in 954. After Burchard died, Otto II appointed Liudolf's son Otto to succeed him.

Swabia showed its strength yet again in 1027 when Duke Ernst of Swabia revolted against Conrad III. The king countered by allying with the counts in Swabia and thus quickly ended the episode. By 1039, Swabia was one of four duchies in the king's hands.

From 1077-1080, Germany was roiled by the Investiture Contest, a competition between king and pope, which left local lords unchecked and free to engage in a massive land and property grab, especially regarding monasteries. The duke of Swabia, Rudolf, was even elected the anti-king during this time, but never gained widespread acceptance.

Following the Contest, true feudalism sprang up in the form of castlebuilding all over Swabia and the rest of Germany. One of the most prominent was its duke, Frederick of Staufen, or Hohenstaufen. The Hohenstaufen family were very powerful and provided Swabia with its most illustrious dukes. Thus when King Henry IV was seeking supporters during the civil wars, Duke Frederick I was a natural choice to marry his daughter. After the failure of Henry's dynastic line in 1138 and the reign of two interim rulers, a descendant, Duke Frederick III, actually vaulted to the kingship, which the family held until 1250. Meanwhile, Frederick, now King Friedrich I Barbarossa, continued to build up Swabia to strengthen his position against the still-powerful dukes such as Henry the Lion, a practice which brought him into some conflict with the Bertolds.

After the Staufens, the Bertolds were the most prominent family of castlebuilders in Swabia. This family drew their early power and tax base from their control of monasteries, which they founded in the hitherto-uninhabited Black Forest. Once developed by monks, it began to be colonized and towns laid out, including Freiburg-im-Breisgau, founded by Conrad Bertold in 1120. By then, the castle had become so important that their owners began to name themselves after them, so it is as Conrad von Zähringen that Conrad appears in the records.

But as the castles went up, the duchies went down under this wave of particularism. After the Hohenstaufens fell out of power, Swabia was given to King Conrad III's son. After his death, it returned to the crown and was put in control of ministeriales, a non-noble class of civil servants. The idea was that such men would be more tractable and less likely to alienate the fief from the crown out of their own greed. It is perhaps a recognition of the lesser power of the ministeriales that at the same time, the Zähringen family was also restricted in 1169 in terms of their activities in Burgundy. When the Hohenstaufen line entirely failed in 1268, it signaled the breakup of Swabia as a political unit as various portions were snapped up by families which were to play important roles in Germany's future: Zähringen, Habsburg and Hohenzollern. Eventually, the margraves of Baden, located along the Rhine River and those of Württemberg, centered at Stuttgart (also Stuegart, Stuggart, Stuhgart, a Swabian word meaning "stuten garten" or Mare's Corral) became dominant. The idea of Swabia was not lost, however, and in 1376, 14 cities, for their own protection, organized themselves into the Swabian League of Cities. The League grew to eventually include over 32 cities from Basle in the west to Regensburg in the east, from Constance in the south to Nuremburg in the North. In 1488, a new grouping, now simply styled "Swabian League" was formed by these cities, the larger principalities and even individual knights, for the purpose of maintaining internal stability. When in the 16th century, the Holy Roman Empire began to organize around the Kreis, literally, "circle", these states called themselves the Swabian Kreis.

The Kreis, more properly the Reichskreis or Imperial Circle, was an area similar to an English county within the larger whole. (The term originally originally referred to a a lined-off place were a battle was to take place. Within such a ring, different rules applied as compared with the outside of the ring.) The Kreis designated the Swabian Kreis comprised all of the inheritor Swabian states. In the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as areas of eastern Europe were conquered from the Ottoman Turks, many from Swabia migrated to areas in the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires. The Danube River, or Donau, was the most frequently used means of transportation for the trek and this group came to be known as the Donauschwaben.

Today, the term Swabia is still sometimes used to refer to the areas once encompassed by the medieval duchy. The modern center is more thought to lie at Stuttgart and here and there one can still often hear spoken the Swabian dialect, Schwäbisch (Schwobisch) with its customary friendly greeting of "Grüss Gott".

Genealogical and Historical Records

Most researchers are probably not at the point of conducting genealogical research into medieval Swabia and should probably consult the information available on Baden, Württemberg, and Baden-Württemberg. It is also possible that a reference to Swabia may actually be in present-day Bavaria, see here: Schwaben (Swabia), Alsace or Switzerland.

Genealogical research in the medieval period in any place can be both quite difficult and different than for subsequent periods. Apart from the nobility, surnames were not yet generally in use, nor were, as a rule, parish records maintained. Thus, medieval researchers must employ a much different set of tools and resources. Should you have traced your heritage back to medieval Swabia, however, the best place to start is probably the USENET newsgroup soc.genealogy.medieval where you will find other researchers with advice and similar goals.

Atlases

Historischer Atlas von Bayerisch-Schwaben, im Auftrag der Schwäbischen Forschungsgemeinschaft, unter Mitwirkung der Kommission für Bayerische Landesgeschichte, Wolfgang Zorn, (1982-1990, Augsburg: Verlag der Schwäbischen Forschungsgemeinschaft ; Weissenhorn: Auslieferung, A.H. Konrad. Scales differ. Series title: Veroffentlichungen der Schwäbischen Forschungsgemeinschaft bei der Kommission für Bayerische Landesgeschichte)

The Anchor Atlas of World History, volume I, Kinder, Hermann and Werner Hilgemann, (1974, New York: Anchor Books/Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-06178-1)

Bibliography and Literature

English:

Aufrere, Anthony, A warning to Britons against French perfidy and cruelty: or, A short account of the teacherous and inhuman conduct of the French officers and soldiers towards the peasants of Suabia [sic], during the invasion of Germany... (1798, London: T. Cadell; 1954, Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer Series title: Darstellungen aus der Wurttembergischen Geschichte; Band 39)

Barraclough, Geoffrey, The Origins of Modern Germany (1966, New York, Putnam)

McCardle, Arthur W., Friedrich Schiller and Swabian Pietism, (1986, New York : P. Lang; Series title: American university studies. Series I, Germanic languages and literatures ; vol. 36)

Musset, Lucien, The German Invasions, The Making of Europe 400-600 A.D. (1993, New York: Barnes and Noble Books)

Ozment, Steven, The Burgermeister's Daughter: Scandal in a Sixteenth-Century German Town (events in the town of Schwäbisch-Hall) ISBN 0-060-97721-3

Reuter, Timothy, Germany in the Early Middle Ages / 800 - 1056 (1991, London and New York, Longman)

Sabean, David Warren

Kinship in Neckarhausen, 1700-1870 ISBN 0-521-58657-7

Property, Production, and Family in Neckarhausen, 1700-1870 (A good view of the government, farming practices and private life in a small village, based on a fifteen-year study of documents from many sources.) ISBN 0-521-38692-6

Walter, Jakob, The Diary of a Napoleonic Foot Soldier (Walter was conscripted into Napoleon's army from a small Württemberg town just in time to take part in the march to Moscow.) ISBN 0-140-16559-2

In German:

Baumann, Franz Ludwig, Die gaugrafschaften im wirtembergischen Schwaben. Ein beitrag zur historischen geographie Deutschlands (1879, Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer)

Birlinger, Anton,

Aus Schwaben: Sagen, Legenden, Aberglauben, Sitten, Rechtsbrauche, Ortsneckereien, Lieder, Kinderreime : neue Sammlung, (1874, Wiesbaden: H. Killinger)

Schwäbisch-augsburgisches Worterbuch (1968, Wiesbaden: M. Sandig)

Schwäbische volkslieder. Beitrag zur sitte und mundart des schwabischen volkes (1864, Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder)

Blezinger, Harro, Der Schwäbische Stadtebund in den Jahren 1438-1445, mit einem Überblick uber seine Entwicklung seit 1389 (1954, Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer; Series title: Darstellungen aus der Wurttembergischen Geschichte; Band 39)

Buttner, Heinrich, Schwaben und Schweiz im fruhen und hohen Mittelalter; gesammelte Aufsatze. (1972, Sigmaringen: J. Thorbecke; Series title: Vortrage und Forschungen; Band 15)

Eberl, Immo, Wolfgang Hartung und Joachim Jahn, Fruh- und hochmittelalterlicher Adel in Schwaben und Bayern (1988, Sigmaringendorf: Glock und Lutz; Series title: Regio Band 1)

Fried, Pankraz, Forschungen zur schwabischen Geschichte (1991, Sigmaringen: Thorbecke; Series title: Veroffentlichungen der Schwäbischen Forschungsgemeinschaft bei der Kommission für Bayerische Landesgeschichte)

Nubling, Eduard, Studien und Berichte zur Geschichts-, Mundart- und Namenforschung Bayerisch-Schwabens: Festgabe zum 80. Geburtstag des Verfassers (1988, Augsburg: Schwäbische Forschungsgemeinschaft; Series title: Veroffentlichungen der Schwäbischen Forschungsgemeinschaft bei der Kommission für Bayerische Landesgeschichte)

Pflug, Johann Baptist, Erinnerungen eines Schwaben, 1780-1830: Kulturbilder aus der Kloster-, Franzosen- und Rauberzeit Oberschwabens, nach den Erinnerungen des Maler-Romantikers Johann Baptist Pflug, (1936, Ulm-Donau: Hohn)

Schwarzmaier, Hansmartin, Staufisches Land und staufische Welt im Übergang: Bilder und Dokumente aus Schwaben, Franken u.d. Alpenland am Ende d. stauf. Herrschaft (1978, Sigmaringen: Thorbecke)

Ziegler, Adolf Wilhelm, Forschungen zur bayerischen und schwabischen Geschichte (1961, München: F. X. Seitz; Series title: Beitrage zur altbayerischen Kirchengeschichte; 22 Band, 1. Heft)

Zotz, Thomas L., Der Breisgau und das alemannische Herzogtum: zur Verfassungs- und Besitzgeschichte im 10. und beginnenden 11. Jahrhundert (1974, Sigmaringen: J. Thorbecke; Series title: Vortrage und Forschungen. Sonderband; 15)

Video:

Auf der Schwäbsche Eisebahne. A Festival of the Swabian Spirit, This video presents an extravagant production of brass bands, folkdancers and groups set against lush scenic backgrounds of the Swabian and Black Forest regions. Choirs and musicians perform some of your favorites like "Schaffe, schaffe Hausle baue" and many more. 60 minutes. German language. TYROL International: #1109, $25.00. NTSC American Format. Phone: 800-241-5404 (USA).

Calendar

In some records you may find alternate names for the months. These are Germanic names, established by the Emperor Charlemagne in the 800s:

January = Hartung, also Horn, grosser Horn and Jänner (sometimes written Jenner). Jänner is still in use.

February = Hornung, also kleiner Horn, sometimes Hornig (in the Sundgau)

March = Lenzig

April = Ostermond

May = Maien

June = Brachet

July = Heuert

August = Ernting

September = Scheidling

October = Gilbhard

November = Nebelung

December = Christmond

databases Literature-DB

Iscriviti a:

Commenti sul post (Atom)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento